Search our Archives:

» Home

» History

» Holidays

» Humor

» Places

» Thought

» Opinion & Society

» Writings

» Customs

» Misc.

|

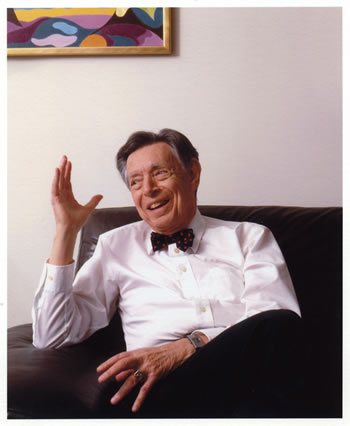

Robert O. Fisch, M.D.

By Phil Bolsta

For Previous Page, go to Page One

As we climbed toward the mountain pass in the Alps, we were ordered to stop and form lines of five. At the pass, two were randomly shot from each line. As some fell, the rest kept marching. Soon, we arrived at Mauthausen, the largest concentration camp in what is now Austria, but was then part of Germany. Our daily food ration there was a cup of black coffee and a quarter slice of dark bread covered with green fungus.

After just four days, we left Mauthausen because the Russians were nearing the camp. Those who were too weak to walk were put on pallets rigged to horses. When we got to the Gunskirchen concentration camp in the German forest, the exhausted prisoners were thrown directly into open graves, then shot. The barracks at Gunskirchen were packed so tightly that we had to spend each night squatting, crammed together knee to knee. During the night, the weaker prisoners toppled over on others. Many were suffocated.

For the thirty thousand prisoners in Gunskirchen, there was one latrine for twelve men and sixteen women. We could only go there during six specific hours each day. Anyone who urinated or defecated at any other time was executed on the spot. One day, while it was raining, I left the barrack and tried to urinate under my coat. A German noticed me standing there in the rain, although fortunately he didn't notice me urinating. He beat me with his rifle until I collapsed. I didn't leave the barrack to urinate again, I can tell you that.

When we found out on May 1 that the Russians had occupied Berlin, we were absolutely ecstatic. But then the next day the Nazis killed us the same as if it were any other day. On the heels of such hope, our despair became even more profound. The end seemed so close, yet so far away. We also learned of a standing order: If enemy troops were approaching, the prisoners would be machine-gunned and the camp burned down.

When the Americans liberated us on May 4, we were all just bone and skin. If it had been another week or so, I wouldn't have been alive. I'm quite sure of that. I was so weak, I couldn't even leave the barrack. When I finally could, I had to crawl over steps, since I could not bend down and still keep my balance.

More prisoners died on that liberation day than any other day. It's like a marathon runner who gets to the very end and then collapses. They ran 26 miles, they were told we won the war, and they collapsed and died. We had known the end was coming — that was the only thing that had kept us going. Otherwise, it would have been hopeless.

The day after we were liberated, the American who found us stopped me and asked me why we were treated like this. I said it's because we are Jewish. He could not believe it. It was incomprehensible to him that human beings could do this to one another just because they were a different religion.

A few days after we were liberated, a dirty, hungry German soldier came to me, begging for food. I was filled with hatred for the Germans. I wanted to kill them all. But I had to make a choice. I asked myself whether I should do to him what they had done to us, or if I should do what my father would have done. I gave him some food.

Fifty years later, I attended the fiftieth-anniversary celebration of the liberation of the Gunskirchen concentration camp and I talked again with the American who had liberated us. His name is Dale Speckman. He had gotten lost on his jeep in the forest, smelled something horrible, and was curious what it was. When he opened the gate, the prisoners cheered him and crawled on him. He said he could not get the smell off his clothes for weeks. He threw the prisoners his cigarettes and the little food that he had, and they ate the cigarettes. They crawled to the bushes outside the camp and started to eat the leaves. At the anniversary ceremony, Speckman placed a yellow-star wreath at the site.

When I returned to Budapest in July, I went to our home and found my mother there. She had been hiding with Anna, the nurse who had lived with us. It was wonderful to see her again, but emotionally, I was so burned out, I was practically a robot. It took me months before I started to have some feelings again.

Except for my mother, Iren, and older brother, Paul, who had been sent to school in Switzerland in 1938 because of the political unrest, all my relatives were exterminated. An eyewitness told me later of my father's fate. Before he was taken to a concentration camp my father, Zoltan, gave his food to the needier ones, explaining, "I always have enough." Eventually, he starved to death. He was so greatly respected in the camp he was in that he was the only one not buried in a common grave. We brought his body back, and he was the first to be buried in the memorial cemetery in Budapest.

They say that one man's death is a tragedy, one hundred deaths a disaster, one thousand deaths a statistic. Out of 600,000 Hungarian Jews, only 80,000 had survived. At the cemetery where my father is buried, there are many gravestones. As people walk through it, they see one stone that reads, "Here are 10,000." Another reads, "Here are 20,000." And so on. At the exit is a stone that reads, "Here is one." According to the Talmud, "Whoever destroys the life of a single human being, it is as if he had destroyed an entire world." The death of my father was the death of my world as I knew it.

Today, I have a very interesting life. First of all, I'm an extremely happy person. Experience has shown me that in order to really enjoy things, you have to go through some hardship. The only time you really appreciate your health, for example, is when you are sick — until then, you don't know what you had. Because of the hardship I went through, I look at every minute as a gift and I enjoy life tremendously. When I put a potato in a microwave, that to me is a joy. For most people, it's just a potato. At night, however, I still have bad dreams. In my dreams, I've died a hundred times. Sometimes I feel like I'm dreaming during the daytime.

Through the Yellow Star Foundation, which was established by a friend of mine, Erwin Kelen, I've given hundreds of lectures in schools and other places — mostly in Minnesota but also in Europe and Israel. I tell young people about my experiences in the Nazi death camp so that they can learn from it. Otherwise, I don't like to talk about it.

In my lectures, I tell students that they have to make a choice. Are they going to be humanistic or animalistic? You cannot expect the world to change, you can only change yourself. And hopefully that will be enough to change others. It's very rewarding to have such an impact on young people. I've received honorary degrees in other countries because of my work in medicine. But this is more important to me.

All of us who were marked by the yellow star were tattooed inside. As survivors, we have a special obligation, not a privilege, in being alive. We must take a stand against suppression and injustice. Our standards have to be based on principles, not practicalities. We who survived are not different from others, we just played a special role in a special time. One night in a dream, I asked God, "Are we the chosen people?" The answer I got back was, "The world turns on its axis and each segment receives an equal share of sunshine."

Next month, I'm going back to Hungary to give a talk at the Holocaust museum in Budapest. This museum was actually the synagogue I grew up in. On the wall, it reads, "Love your neighbors as you love yourself." When I returned there last year and saw those words, which had been there when I was growing up, it really shook me and made me cry. Reading it again after all these years meant a very different thing than it did before the war.

I subtitled my first book "A Lesson of Love from the Holocaust" because the Holocaust teaches us that good can be learned from even the worst human tragedies. It is not the ugliness of hate but the beauty of love that survives. What I would like to be remembered is not the horror, but the beauty created by human virtue and how the spirit can be enlightened even in the midst of suffering.

People are often surprised by my attitude toward life. But I ask, what would those silent, slaughtered millions ask us now? To hate and to be unforgiving? Unlikely. I believe they would want us to live with understanding, compassion, and love. The message that I would like to send is: Remain human, even in inhumane circumstances.

* * * * *

For more articles on the Holocaust, see our Holocaust Archives

~~~~~~~

from the February 2008 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|

|

Please let us know if you see something unsavory on the Google Ads and we will have them removed. Email us with the offensive URL (www.something.com)

|

|