Search our Archives:

» Home

» History

» Holidays

» Humor

» Places

» Thought

» Opinion & Society

» Writings

» Customs

» Misc.

|

Violins of Hope" Demonstrate the Power of Memory and Art

By Meg Freeman Whalen

"Wondrous, my child, is the transformation of anguish."

Yiddish poet Abraham Sutzkever presents this testament to redemption more than once in a book of poetry called The Fiddle Rose. In Sutzkever's poems, words of suffering are transformed into words of healing. "Wondrous transformation" is likewise the story of the "Violins of Hope," a collection of violins recovered from the Holocaust and painstakingly restored by the master Israeli violinmaker, Amnon Weinstein.

The son of a violinist/violinmaker who fled Vilna, Lithuania for Palestine in the years before the Holocaust, Amnon Weinstein never met his Lithuanian relatives. Knowing that, like his family, many Jewish musicians and their instruments had been silenced by Nazi brutality, he began a quest two decades ago to find and repair violins from the Holocaust. In 1996, he discovered the first, and now nearly 30 instruments have found their way into Weinstein's shop in Tel Aviv. Some he discovered at flea markets; some were brought to him by family members of the musicians who had owned them. Many of the violins were so damaged from being played outside in rain and sun and snow, that it often took him more than a year to bring each to playing condition. One was filled with ashes.

In April 2012, 18 of the "Violins of Hope" will come to Charlotte, N.C. for their North American debut. First played in Jerusalem in 2008 and never before exhibited and played together in this continent, the violins have extraordinary histories of suffering and survival. Some were played in concentration camps, while others belonged to the Klezmer musical tradition that was nearly destroyed in the Holocaust.

"The first violin I received belonged to fiddler Shimon Krongold from Warsaw," Weinstein said in an interview. "He bought it from violin builder Yaakov Zimmerman, who was my late father's teacher. It was clearly made with great love and attention to minute details in choosing the wood and carving it. Zimmerman worked in the German School style, being one of the very first Jewish violinmakers, since we know that there are no Jewish makers before 1900."

The violin was brought to Weinstein by Edna Rosen and her brother, Nadir Krongold, niece and nephew of Shimon Krongold. Rosen told this story of the violin to Weinstein:

"Sometime after the end of WWII, a man knocked on our home door in Jerusalem. We didn't know him and were astonished to see him holding a violin wrapped in an old blanket. The man introduced himself as an old friend of Shimon Krongold, the brother of our father, Chayim. Father didn't see his brother for many years until the day he was told that his only brother died of typhus in Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

"The man told us that he had met with our uncle in Tashkent, where he came while escaping the German occupation of Warsaw, taking his violin along. Father asked to have the violin, but the man asked for some money in return, as he admitted that our uncle left him the instrument before dying.

We paid the man, who left and never returned. It was 1946 and since then the violin is our treasure, our only inheritance and memory of our lost uncle."

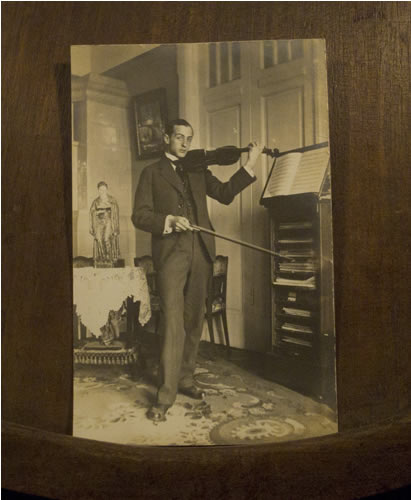

Photo courtesy of Amnon Weinstein

Simon Krongold playing on Krongold violin

Presented by the University of North Carolina at Charlotte College of Arts + Architecture, in partnership with nearly 20 academic and cultural institutions, the Krongold violin and 17 other "Violins of Hope" - now restored to instruments of great beauty - will be brought to life in a series of performances in Charlotte and exhibited in the new UNC Charlotte Center City Building Gallery. A series of related programs, from film screenings to lectures, will allow people of many faiths, young and old, to explore the history of music in the face of oppression and to witness the power of memory and art to transform anguish into hope. For details of the many events or to learn more about the "Violins of Hope," visit www.violinsofhopecharlotte.com.

The story of music in the Holocaust is a complex story. Musical activities took place in almost all of the many installations of the Nazis' vast prison empire, and there was considerable variety in the music performed. Solo musicians, small ensembles such as quartets or quintets, wind bands, choirs, and full orchestral ensembles were among the performing groups. The music ranged from traditional to popular to "classical." In addition, original music was composed in the camps. In Auschwitz, for example, there was a 120-member brass band and an 80-piece orchestra. One of the "Violins of Hope" to be exhibited this spring was played in the Auschwitz orchestra.

The Theresienstadt ghetto had an unusually rich musical environment, with multiple daily performances. Many professional musicians were imprisoned there, including composers Viktor Ullman and Pavel Haas and composer/pianist Gideon Klein, all of whom composed music while at Theresienstadt. Ullman and Haas were later killed at Auschwitz; Klein at the nearby Fürstengrube.

In all the camp environments, music was created under two conditions: forced music-making and self-defined music-making. Music, therefore, was both an instrument of cruel oppression and an instrument of survival, protest, and hope. Musicians in the camps were commanded to perform in multiple settings. Detainees were ordered to sing while exercising, marching, or working. The songs demanded included Nazi soldier songs and folk songs and, as a form of mockery, songs representative of the prisoners' culture and heritage. Those who did not comply, or who sang too loudly or too softly, were beaten. Ensembles of musicians (amateur and professional) performed instrumental and choral music on demand. They performed to entertain officers, to accompany prisoners as they marched to and from work, and to accompany staged executions. Repertoire was often determined by the SS officers, sometimes in consultation with the musicians themselves.

Musicians also initiated music-making, playing music for themselves for entertainment, for comfort, to preserve their cultural identity, and to protest and resist the oppression of the Nazis. Contrary to music on demand, which took place daily, self-defined music-making could take place only during the restricted "leisure" time after the evening curfew or on Sundays. Performances included choral and orchestral concerts, chamber music concerts, cabaret performances, and theatrical presentations.

Music with political content or purpose was forbidden and had to be performed in secret. Much self-determined music-making, however, was done with the approval of the concentration camp directors. Musicians who were allowed to perform on their own initiative were often part of a "privileged" group of prisoners. Being part of a "privileged" class created a complicated psychological situation for some musicians. Their musical skills in some cases allowed for special treatment, which created feelings of both relief and guilt.

By giving voice to the "Violins of Hope," an international array of professional musicians will explore the many facets of music-making in a series of five performances in April 2012. Among them, "Hope in Resistance," on April 12, celebrates resistance activities, from Le Chambon to the Bielski brothers, while "Hope in Dark Places" presents music from Theresienstadt. The performances conclude on April 21 with a concert with the Charlotte Symphony, featuring soloist Shlomo Mintz.

The "Violins of Hope" is a living project that begins a new chapter in North America. By bringing the violins to North America - and first to Charlotte - Amnon Weinstein hopes to discover other instruments with connections to the Holocaust, to reclaim their music and redeem their memories for generations yet to come.

Meg Freeman Whalen is the Director of Communications and External Relations for the UNC Charlotte College of Arts + Architecture. She also teaches in the music department at Queens University of Charlotte.

~~~~~~~

from the November 2011 Edition of the Jewish Magazine

|

|

Please let us know if you see something unsavory on the Google Ads and we will have them removed. Email us with the offensive URL (www.something.com)

|

|